Research at the ACCSTR has provided solutions for critical management issues, such as identification of light sources that prevent disorientation and death of thousands of hatchlings each year and development of methods to evaluate and improve beach renourishment.

ACCSTR Major Accomplishments

(Click on diagram to access the publication).

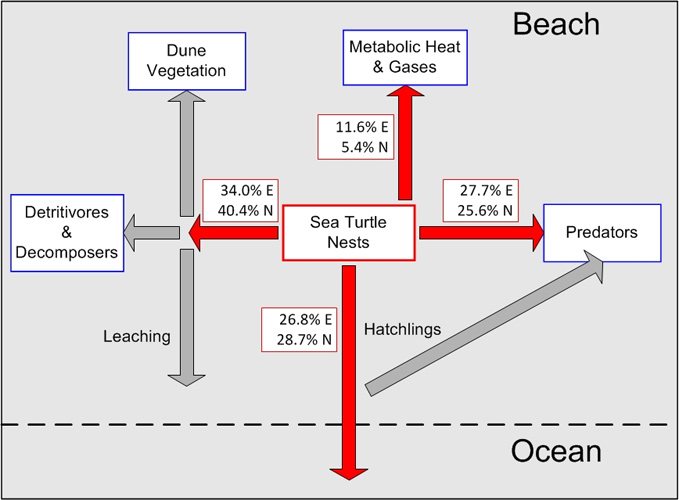

Dune stabilization

We demonstrated that sea turtles play a key role in beach dune conservation by transporting nutrients from foraging grounds to nesting beaches. Nutrients from sea turtle eggs deposited in nesting beaches fertilize dune vegetation, stabilize dunes, and help to conserve beaches around the world for both turtles and humans.

Lighting disorientation

Lighting behind sea turtle nesting beaches disorients thousands of hatchlings each year, causing them to move towards the light – and high probability of death – rather than towards the sea. Our research on the role of light perception in the orientation of hatchlings resulted in a number of practical solutions. We discovered that a specific wavelength of yellow light – the same as that in low pressure sodium lights – does not attract sea turtle hatchlings. As a result, hundreds of low-pressure sodium lights are now used along the Florida coast and thousands of hatchlings have been saved.

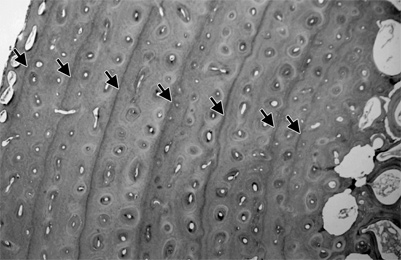

Photo: Alan Bolten

Solving the “mystery of the lost year” for Atlantic loggerheads

To solve the mystery of where the thousands of hatchling loggerheads go when they swim away from Florida nesting beaches each year, ACCSTR affiliates with expertise in genetics, ecology, satellite telemetry and growth models worked together to establish that post-hatchling loggerheads spend the first 10 years of their lives in the open ocean waters of the eastern Atlantic. This was the first documentation of the entire life cycle of a sea turtle. The loggerhead remains the only sea turtle species for which we know the complete life cycle from nesting beach to open ocean developmental habitat and back to near shore developmental habitat.

Growth rates

Our research on growth of green turtles was among the first to demonstrate the very slow growth rates and thus long time to sexual maturity in green turtles. When we began our growth studies, it was believed that green turtles reached sexual maturity in about 6 years. Our work and the work of others have extended these estimates to 30 to 50 years to reach sexual maturity. This difference has tremendous implications for how we conserve sea turtles and how we assess the success of our conservation programs. For example, if a nest-protection program were initiated to increase the number of breeding adults returning to nest, we now know that we would have to wait at least 30 years, not just 6 years, to judge the success of the program. Complementary studies on nutritional ecology have helped us understand the causes of these very slow growth rates.

Population genetics

In our studies of migratory movements of juvenile turtles, we have used both standard flipper tags and genetic “tags.” We were the first to use mitochondrial DNA sequence analysis to demonstrate that a foraging ground population of sea turtles is composed of turtles from several nesting populations throughout their range. Combining our genetic results with tag return data, we have demonstrated that foraging ground populations are a resource shared by many nations and require a regional, multi-national approach for successful conservation.

Setting conservation goals

How many sea turtles are needed to fulfill their ecological roles? How many sea turtles existed before humans began extensive over-exploitation? Our research on the nutrition and feeding ecology of wild green turtles has revealed that a small area of seagrass pasture can support a large number of green turtles, which gives credence to the earlier – almost unbelievable – reports by early Caribbean explorers of vast flotillas of green turtles. Based on our research, we have estimated that current Caribbean green turtle populations represent about 10% of their natural levels. Documenting the drastic decline in green turtle populations generates support for conservation of remaining populations and establishes goals for recovery.

Information and communication systems

To facilitate rapid distribution of information, we developed and manage CTURTLE, an internet listserv discussion group on sea turtle biology and conservation with over 1600 subscribers from over 60 different countries. In addition, we developed an online bibliography of all sea turtle publications now numbering greater than 21,000.